How is the resourcing of the health workforce expected to evolve for Manatū Hauora in the future?

Healthcare workforce planning in New Zealand has often operated on a cycle of 'neglect, panic, repeat'. Typically, a significant event triggers heightened focus and increased funding. However, as the immediacy of the event diminishes, attention from policymakers and the public shifts away, leading to a reduction in funding and focus until another critical event occurs.

The New Zealand health system benefits from a dedicated and highly skilled staff who consistently deliver exceptional care. However, for many years, the growth and support for this workforce have not kept pace with needs. This shortfall is attributed to several factors: the lack of quality data which hampers the system’s ability to define its workforce requirements, chronic underfunding linked to this data deficit, and the fragmentation among former district health boards. This fragmentation has hindered the ability to achieve economies of scale and optimize the use of the available workforce, occasionally fueling domestic competition for health professionals. Additionally, global shortages of health workers have increasingly compelled New Zealand to vie with other countries for these essential personnel.

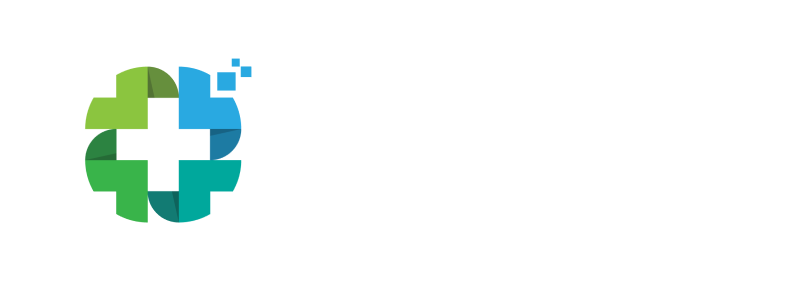

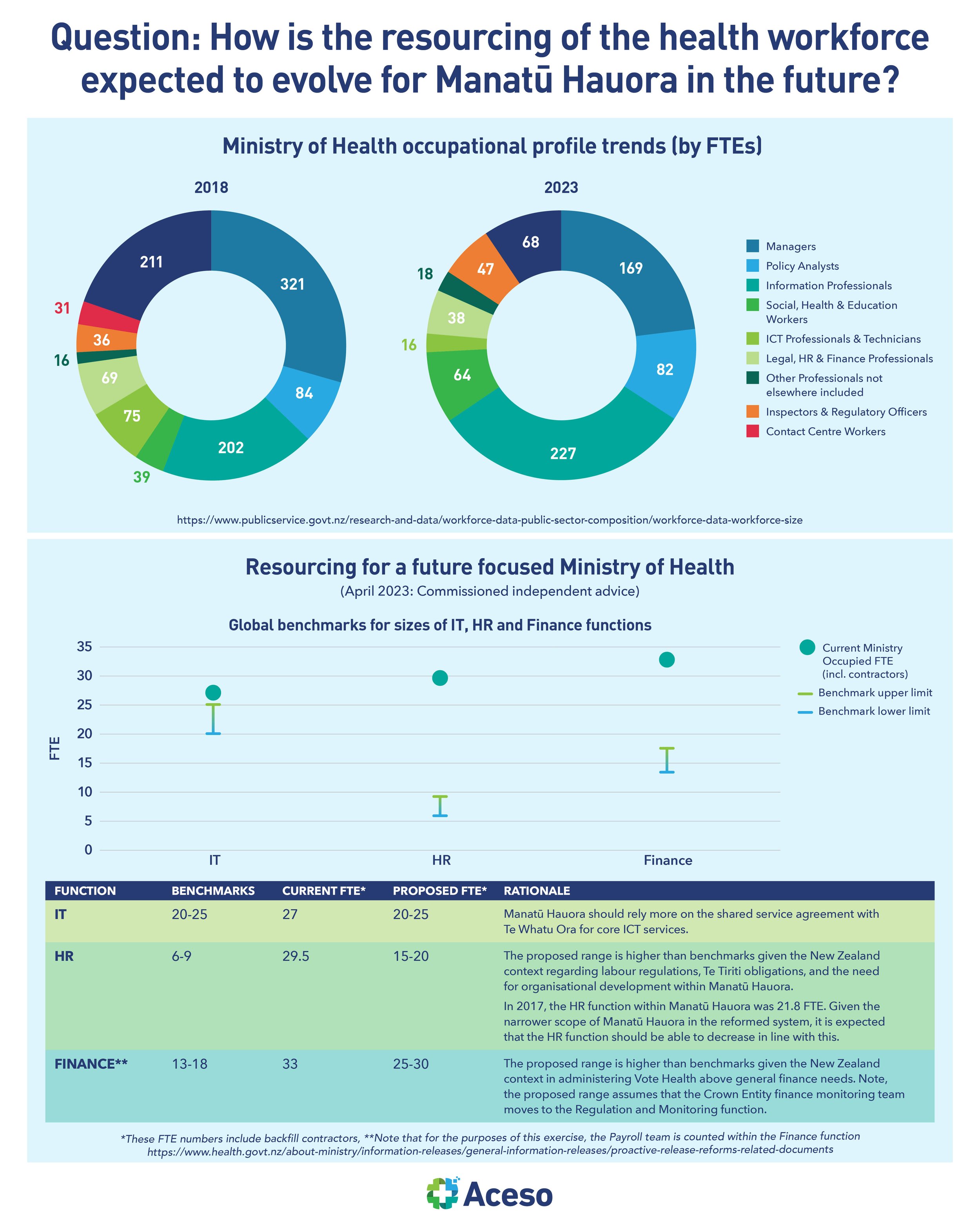

An independent report commissioned by the Ministry of Health in 2023 noted that based on high-level analysis and benchmarks, Manatū Hauora should consider working toward an overall size of 550-600 FTE (including contractors) over the next three years. It went on to state that the recommended size ranges are based on high level analysis and benchmarks of other similar public sector organisations. Manatū Hauora would need to complete a more in depth review of roles and efficiency of their processes to confirm the target range and implementation approach. As of February 2023, the size of Manatū Hauora was 758.64 FTEs. Based on expenditure to date, Manatū Hauora was forecast to spend 29% ($56.9m) of its departmental operating expenditure on administrative and support services in FY23. This is much higher than the public sector average of 18% as benchmarked by Treasury for the five broad corporate and executive functions.

A reimagined workforce would begin with sharing a clear and compelling change narrative that describes the rationale for change. Establishing benchmarking to understand the efficiency of processes and activities compared to international standards would be a subsequent step. Additionally, a prioritised and sequenced list of key process optimisation opportunities across Manatū Hauora would include the use of technology to improve the efficiency and standardisation of processes.

In addition to enumeration, a number of other issues also perpetuate the vulnerabilities of the health workforce and ultimately the impact on the public health system as a whole. More research and consideration must be given to this issue, as a matter of urgency.